The Targa Florio

A brief history of the greatest road race in the world

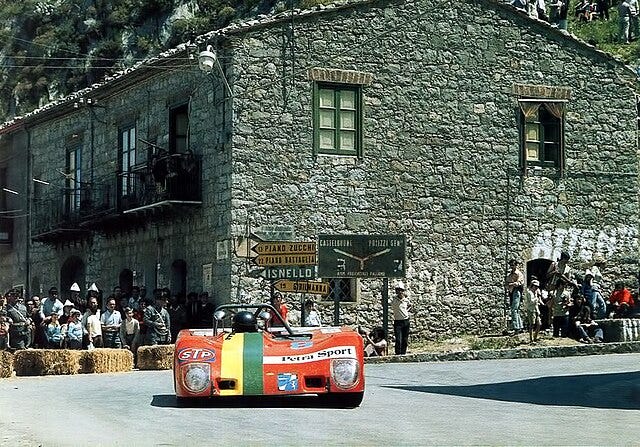

From 1906 to 1977, the grand Madonie Mountains to the east of Palermo pulsed with the sound of racecars carving up and down their treacherous cliffside roads. Many of the greatest racing drivers of the twentieth century tested themselves here, slinging Ferraris, Alfa Romeos, MGs, Porsches, and other iconic sportscars around a track comprised entirely of public roads. There was no greater or more venerable challenge in a sportscar than the legendary Targa Florio.

Even though the inaugural Targa Florio was all the way back in 1906, it was hardly the first massive public road race in the world, or even in Europe. In fact, the race’s creator was directly inspired by two particular races that had already run for several years: the Gordon Bennett Cup and the Targa Rignano. The Gordon Bennett Cup (1900-1905) was a series of several hundred-mile-long automobile races across Europe which pitted national auto clubs against each other. It was organized by a man named, as you may have guessed, Mr. James Gordon Bennett Jr., an American newspaper magnate. The Targa Rignano was a motorcycle and automobile race between Padova and Bovolenta in Italy’s northeastern Veneto region which ran from 1900 to 1908 and was named after Count Rignano, the title sponsor of the race.

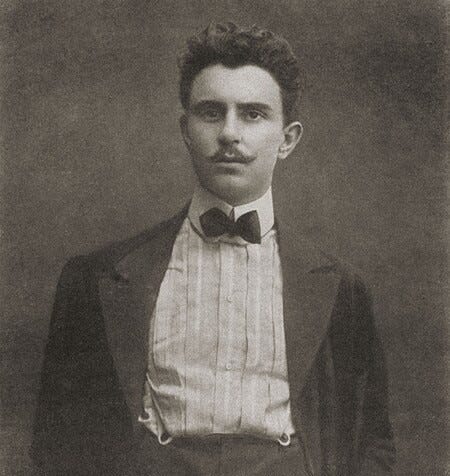

Vincenzo Florio Jr. wished to see the burgeoning world of motorsport lend its excitement and prestige to his hometown of Palermo, Sicily. Signore Florio, luckily, had the resources to initiate such an event. He was the grandson of Sicily’s version of Andrew Carnegie, Vincenzo Florio Sr. The Florio family were perhaps Sicily’s most prominent through much of the 19th century. They were involved in everything from tuna canning to winemaking to shipbuilding and even sulfur mining.1

Vincenzo Jr. was a motorsport enthusiast. He had even won the 1903 Targa Rignano and consulted with Mr. Bennett Jr. on how to execute a similar event to his much beloved Cup races. And thus, the Targa Florio - roughly meaning Florio Trophy - was born, inviting those who dared to race through the beautiful Sicilian mountain ranges.

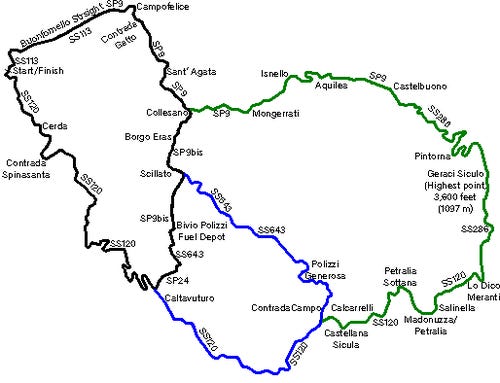

The inaugural TF was a three-lap circuit, each lap covering 91.3 miles of entirely dirt roads.2 Ten cars finished the race, which was won by Alessandro Cagno driving an Itala. Don’t worry, it’s not important to know who that is; I’d never heard of him either. The race lasted about 9 hours and must have been terribly uninteresting for spectators since one can only see a sliver of the 91-mile circuit at any given point and there were so few cars. But it was certainly a profound challenge of focus and endurance for the drivers, and a test of reliability for the cars.

The race was considered a great success and continued each year until 1915. It was paused for the next few years as Italy was busy doing something, I haven’t looked up what. But the TF returned in 1919!

From 1919 onwards, the race ran over a shorter circuit, this one a mere 67.1 miles. It was shortened again in 1932 to make it cheaper to run by reducing the road maintenance requirements. Now less than half of its original length, the 44.7-mile circuit was called the Piccolo Madonie. Evidently, Mussolini himself signed off on the redesign and ensured the race had the materials needed to build and maintain its course.3 It was this 700+ corner circuit that became the permanent circuit for the Targa Florio.

The race was paused again from 1941-1948 while the Italians were again collectively doing something that I haven’t researched. I think it involved the Germans?

In any case, whatever they did required a few years to recover from. But once the race was restarted in 1948 it ran until 1977. And, in 1955 it became an official event for the Federation International de l’Automobile’s World Sportscar Championship, bringing even greater fame and prestige to the race.4

Vincenzo Florio Jr. died in 1959, having watched the development of motoring and motorsport happen right in his backyard. Some of the most famous names in all of racing history sought the glory of the Targa Florio. Sir Stirling Moss, Juan Manuel Fangio, Graham Hill, Dan Gurney, and Tazio Nuvolari are just some examples.

Even as cars evolved from the boxy carriages of the early 1900s, to the chitty-bang-bangs of the 1920s, and to the sleek sportscars of the 50’s and 60’s, the Targa Florio remained a serious test of mettle and metal. But why was this race so especially prestigious? Is it the danger?

On its face, the TF is not a uniquely risky road race. The Mille Miglia, another legendary Italian road race, was longer, faster, and also took place on open public roads. The Isle of Man Tourist’s Trophy motorcycle race is a similar length to the TF and is significantly more dangerous as motorcycle riders are less protected than automobile drivers. But far fewer motorsport fans know anything about Isle of Man. If you’ve never heard about it or don’t know much, I’d encourage you to read this article:

The Most Dangerous Race

It’s a beautiful day in late May. The sun is shining, and the weather is pleasant. The idyllic, rolling hills of the Isle of Man, a small island in the Irish Sea nestled between Northern Ireland and …

No, I don’t think the danger of high-speed racing is the reason for the Targa’s fame. In fact, I think it’s the opposite. The challenge of racing through Sicily is that you actually can’t go very fast.

The Targa Florio required a serious caliber of finesse and focus. Drivers were in a constant state of activity for several hours. You kept your eyes glued to the road, looking as far ahead as the twisting, rising, and plunging landscape allowed you to while also watching for the slight bumps and cracks in the road that could unsettle the car. Your arms grew sore from the flurry of gear shifting and wheel turning. And your mind became so strained from concentration that it would make you physically exhausted; as if you’re burning more calories from just focusing as hard as you possibly can, trying to remember every piece of the 44-mile circuit so that nothing surprises you. Even a small surprise, such as a corner being tighter than it looked, or an unexpected crest in the road, could lead to disaster. Indeed, several lives have been lost in the Circuito Madonie - drivers who careened off the road and tumbled down any number of the many cliffsides.

Completing the Targa Florio must have felt like completing a marathon. Except this marathon took 50% longer than the average marathon. Drivers were drawn to the Targa Florio for its alluring blend of fame, prestige, and physical challenge. Competing in the TF attracts the same type of individuals who might wish to summit the world’s tallest peaks. There are those among us who are magnetically drawn to severe challenges. And, while the TF ran through some of the most beautiful pieces of Sicily, the irony of the race was that drivers had to completely ignore the natural beauty of their surroundings and instead focus only on the road ahead of them.

So, why did it end?

Cars got too fast. It sounds like a joke, but that was the reason that the FIA took the event off its World Sportscar Championship calendar in 1973. The FIA was concerned that the track was incompatible with the extremely powerful racecars that now dominated sportscar racing. Cars were larger and faster than they’d ever been, and the tight winding roads of the Piccolo Madonie circuit were often hardly wide enough for two Ferrari 312s to drive side by side. It just didn’t make sense.

What’s interesting about this decision is that driver safety was not of particular interest to the FIA in the 1970’s. It wasn’t until the mid-1990’s that motorsport safety began to evolve most rapidly. 1973 was a black year for the FIA’s premier series, Formula 1. The horrific deaths of Francois Cevert and Roger Williamson in F1 that year didn’t lead to any changes in F1’s safety regulations. So, I find it incongruous that the Targa Florio was removed from the FIA’s roster for safety concerns.

Despite being dropped from the FIA’s calendar, the Targa Florio continued until 1977. Even while it was part of the sportscar championship, the race itself was always organized by the Automobile Club di Palermo. So, the Club tried to keep the party going. While the TF had always attracted predominantly Italian drivers and teams, being part of the FIA’s championship had ensured greater attention and a reliable crop of works teams from major manufacturers. Without those things, the Targa Florio simply petered out. Entrants shrank, manufacturers slipped away, and fewer spectators showed up.5

The final nail in the Targa’s coffin was, like the end of the Mille Miglia, several actual coffins. In 1977, an Osella racecar which had already been damaged and should have been black-flagged to stop racing veered off the course and struck a crowd of spectators, killing two and injuring more. The police stopped the race immediately and from then, the game was up - the Targa Florio was done. While it was miraculous that so few drivers and spectators had been killed in the Targa Florio over the course of its 61-year life, the government’s tolerance for this type of risky event had run out. Though, compared to F1, IndyCar, or especially the Isle of Man, the Targa Florio’s list of fatalities is remarkably short. Just 9 people had been killed on the Circuito Madonie since 1906: 5 drivers, a riding mechanic, and 3 spectators.

Nonetheless, I believe it would have been only a matter of time before the Targa Florio resulted in a true catastrophe similar to the final Mille Miglia, or even akin to the 1955 Le Mans disaster where over 80 spectators were killed when a car flew into the crowd. I suspect that if the TF had not ended in 1977, it would have eventually ended later that decade or in the 1980’s with an even more severe loss of life, as there was little to no restriction on spectators positioning themselves at the fringes of the course and the cars were only getting faster.

Could the Targa Florio ever come back? It’s certainly possible but it would take massive investment from either the Italian government or a private entity seeking to resurrect the race. Sicily’s roads are pockmarked and at present are not safe for high-speed driving. It would require some serious infrastructure upgrades to be able to host an international race. For now, those who wish to relive the glory days of the Targa Florio can go to Palermo, rent a Fiat, and send it across the Piccolo Madonie, whose route is still demarcated with road signs.

There are other somewhat similar races that still happen today, like the Pike’s Peak Hill Climb in Colorado or the aforementioned Isle of Man TT, so there’s clearly still an audience of both spectators and drivers seeking the unique dangers of road racing. And while I’m no anthropologist or even an actual historian, I know enough to know that there always will be.